Two weeks after graduating from Carleton College with a major in history, Bill Moseley was a newly-minted Peace Corps volunteer on his way to the arid, landlocked West African country of Mali.

Bill Moseley

Bill Moseley

Living in a small village, learning the local language – “Nobody else spoke my languages,” he noted, “so if I wanted to eat, I had to learn it” – and working as an agricultural extension agent, Moseley discovered his passion for international development and for Africa. “I just fell in love with the way people were managing their resources under very difficult circumstances,” he said.

Today, he’s a professor of geography at Macalester College, but that early experience working alongside farmers in Mali still resonates across the years in his teaching and research.

In January, Moseley will return to Africa – as he has many times in the past two decades –when he serves as the Faculty Director of ACM’s Botswana: University Immersion in Southern Africa program.

Connecting academic work to the real world

Moseley’s practical, on-the-ground approach to learning will be in evidence as soon as the students arrive in Gaborone, Botswana’s capital city and home to the University of Botswana (UB), the host institution for the program.

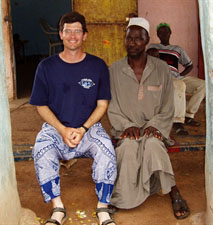

Bill Moseley on a trip to Mali in 2007.

Bill Moseley on a trip to Mali in 2007.

“One of the first exercises I hope to do is to have students go out and visit different marketplaces and to interview vendors, just to get them familiar with the urban landscape,” Moseley said. “Gaborone has different types of markets in different parts of town, from shopping centers to more traditional African markets. The assignment is going to get students on public transportation and interacting with people. Hopefully, as the semester goes on it will make them more at ease about getting out and not just staying on the university campus.”

A human-environment and development geographer, Moseley takes an interdisciplinary approach in the classroom, and has taught courses at Macalester that are cross-listed in environmental studies, international studies, and African studies. Some of the courses have included case studies drawn from Botswana.

As Faculty Director, he will teach a course on “Globalization, the Environment, and Development in Botswana” and will supervise the students in their independent study projects. Students also study Setswana language and choose an elective course at UB.

“I worked for 10 years in development, in the NGO [non-governmental organization] world and then in the government, before I became an academic,” Moseley said, “and one of my master’s degrees is in public policy. I’ve had a longstanding interest in practice, and I’m very keen to connect academic work to the real world. That really influences the way I teach.”

Focus on three pillars of the economy

Moseley’s course will be organized around what he calls the “three pillars of the Botswana economy” – diamond mining, ecotourism, and, most traditionally, the cattle industry. Each pillar will be introduced through a combination of reading and study, followed by field trips to a diamond mine, the Okavango Delta and the Kalahari Desert, and rural areas for firsthand observation.

Visiting a game reserve in Botswana.

Visiting a game reserve in Botswana.

“When I previously taught in South Africa on a Macalester off-campus study program, that was one of my favorite dimensions,” he said. “You could read about it, you could talk about it, and then you could actually go out and see it. It gives students a chance to ask questions of people on the ground.”

“The really exciting thing about Botswana,” said Moseley, “is that Africa typically gets a lot of bad press. Botswana is considered to be a development success story. When it became independent in 1966, it was probably by far the poorest colony that Britain had at the time. It had no infrastructure, and I think it had 16 people with college education. No one ever dreamed that it would become a middle income country, which it is today.”

Astute leadership and good decisions have been the keys to Botswana’s success, according to Moseley, as the country has used revenues from diamonds to invest heavily in education and infrastructure projects.

A cabbage farmer on the outskirts of Gaborone.

A cabbage farmer on the outskirts of Gaborone.

Moseley is planning field trips to take the students to rural areas so they can see the contrasts with Gaborone, where they spend the bulk of the semester. Wherever the students go, the course in Setswana, the national language of Botswana, will help them gain a deeper understanding of the country. “I think learning a local language is incredibly important for connecting to people,” Moseley said. “Even if you don’t master it, even if you just learn basic greetings, it opens up all kinds of doors.”

Beyond the Director’s course and Setswana instruction, students have flexibility to pursue their particular interests through their independent study projects and an elective course at UB. “The course can be in any field,” said Moseley. “If their thing is African music, they can take a music course. If it’s sociology or biology, they can do that.”

Off-campus study leads to a career

An off-campus study program in France was pivotal in putting Moseley on the path to his career. His French host family had spent a lot of time in Morocco, he said, which piqued his interest in Africa and was a factor in his decision to apply for the Peace Corps.

After his two year stint in rural Mali, Moseley decided to pursue a career in international development, and went to the University of Michigan for applied master’s degrees in International Public Policy and Environmental Policy.

A typical rural Botswana home in a small village north of Gaborone.

A typical rural Botswana home in a small village north of Gaborone.

“My first job [after grad school] was with Save the Children (UK), which is a British NGO,” Moseley said. “They sent me back to Mali, but then I was in Zimbabwe, Malawi, and Lesotho.” He returned to the U.S. to work with the Agency for International Development (USAID), earned a Ph.D. in geography at the University of Georgia, and landed at Macalester in 2002.

“My wife and I wanted to settle down and start a family, and academia was a way I could stay engaged with development issues but have a slightly less ‘adventurous’ life,” he said. “But for me, that earlier career really influences and informs my teaching.”

Moseley’s practical experience in managing development projects, and knowledge of how those projects fit within the broader scope of international economic development and public policy, have spurred him to write numerous articles and op-eds, give interviews for the popular press, and start writing a blog for the website world.edu.

“I write lots of academic papers, but other experts read those and it’s typically a small audience,” he said. “I think the public debate is enriched when folks who have expertise in a particular area contribute to the discussion.”

Education and development

Moseley pointed out that the University of Botswana itself, where the students live and study, is a symbol of the country’s successful approach to development.

Statue on the UB campus commemorating the establishment of the university.

Statue on the UB campus commemorating the establishment of the university.

“One of my favorite stories is that very early on, the leadership in Botswana decided that education needed to be a priority,” Moseley said. “This is before the diamond money had come on stream, and they were wondering how they were going to build a university. They got all the elders of the country together, and from the poorest to the wealthiest, the people decided that they would donate cattle, with wealthy families donating more than poorer families. They took a huge herd down to South Africa, they sold it, and with that money they initially built the University of Botswana.”

“There’s a lovely statue on the UB campus,” he continued. “It’s right outside of the library, and it’s a man driving his cattle. It looks like he’s about to go in the front door. That statue is in memory of that early sacrifice to establish the university. So from very early on, people realized that to be an independent country you had to have tertiary education. That’s why Botswana is such an interesting place and why I use it in my teaching.”

Photos courtesy of Bill Moseley.

Links:

- ACM Botswana: University Immersion in Southern Africa program

- Course description and syllabus for “Globalization, the Environment, and Development in Botswana”

- Bill Moseley’s bio on the ACM website and personal webpage on the Macalester College website

- Links to Bill Moseley’s op-eds, articles, and interviews in the popular press, his new blog on the world.edu website, and his selected works in the Macalester Digital Commons